Published for the Texas Independent Bar Association

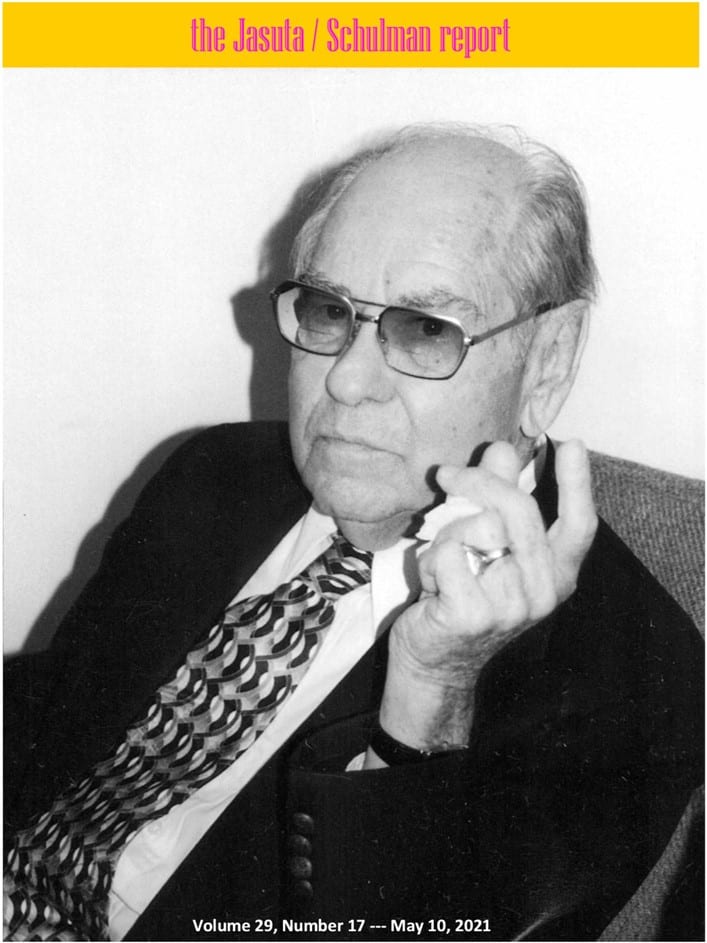

Byron “Lawyer” Chappell was called the grandfather of Lubbock attorneys, and he was one of the most colorful advocates in Lubbock’s legal history.

His more celebrated contemporaries — Travis Shelton, George Gilkerson, Clifford Brown —are considered icons of the Texas criminal bar. But Chappell’s low-key, practical yet zealous, imaginative approach to his craft has inspired Lubbock lawyers for decades.

Chappell was born in Midland in 1916. After obtaining undergraduate and graduate degrees at Texas Tech, he taught school at Lubbock’s Guadalupe Elementary and Carroll Thompson Junior High Schools. His experience teaching minority kids in these low-income neighborhoods was a positive influence on his later career representing Black and Hispanic clients.

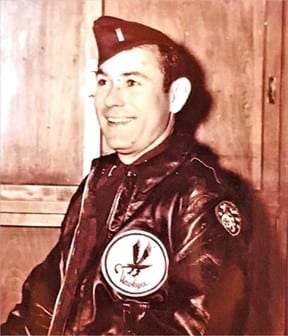

When World War Il erupted, Chappell became a bomber navigator in the U.S. Army Air Corps. His war stories were vibrant but vague, downplaying his heroics while casting himself as a sort of Milo in the novel “Catch 22,” supplying cigarettes, chocolates, nylons and other contraband to fellow servicemen.

Byron Chappell as an Army Air Corps bomber navigator during the second World War. Photo courtesy of Candace Chappell.

After the war, Chappell worked as a shoe salesman in Austin to finance his study of law at the University of Texas. He learned to accurately assess anyone’s shoe size with just a glance, a skill he would one day put to use in the courtroom.

He returned to Lubbock after passing the bar exam in 1948, joining his father Bell Chappell and Roy Carpenter in the practice of law. Soon, his father died and Carpenter left the firm, but he acquired Carpenter’s six- carat diamond ring, which Chappell wore until his death.

Byron Chappell as an Army Air Corps bomber navigator during the second World War. Photo courtesy of Candace Chappell.

Chappell was proud to flash Carpenter’s huge rock, amused when his clients bragged, “My lawyer has a bigger diamond than your lawyer!”

Friday was payday for Chappell’s working-class clients, who often blew their entire weekly wage before Monday. So, on Friday evenings, Chappell boldly drove his pink Chrysler Imperial convertible through East Lubbock, the Guadalupe community, the “Flats” and Slaton’s shadiest neighborhoods, sometimes accompanied by his blonde bombshell wife Rosalie. His clients easily recognized the flashy convertible, ran out to greet their lawyer, and after attorney fee obligations were resolved, Chappell would be on his way.

It may seem amazing his giant diamond ring was never stolen on Chappell’s rounds through these tough environs, but his clients loved him and protected him.

Many stories involve the Lawyer Chappell method of making money. Late one night, Chappell was called to spring a fellow from jail who promised he had cash money. Alas, once the client was sprung, all he had of value were the ostrich-skin boots on his feet. Chappell took the boots and sent him away barefoot. The next morning, the client appeared at Chappell’s office with cash, and the boots were returned.

The day before a negotiated plea of guilty, clients would appear in Chappell’s office to prepare for the court appearance. Sometimes the client would owe a balance on Chappell’s attorney fee. On those occasions, Chappell would tell the client, “The first question that judge will ask you tomorrow will be ‘Have you paid your lawyer in full?”’ (No judge ever asked such a question.)

If all else failed, Chappell forgave the balance due. The charitable gesture encouraged clients to return and refer others. He also represented many indigent clients pro bono.

Chappell, famous for his talent collecting fees, also had talent setting fees. His philosophy was to charge whatever the traffic would bear. “You quote the biggest fee you think the client can pay,” he advised. “Watch the client carefully. If he gasps at your quote, you can negotiate. On the other hand, if the client reaches for his wallet, just say, ‘That will be the down payment.”’

“Many folks accused of crimes are guilty of something, but they are usually over-accused by some stupid prosecutor,” Chappell said. “They’re looking for a fair deal, and they want a lawyer who will fight hard for the best deal available. If you fight hard, you will satisfy your clients. Get the client to pay a fee that will justify your efforts in fighting hard for your client, and you will be successful.”

As a trial lawyer, Chappell won some and lost some, but he always gave his best effort. He rarely handled high-profile cases, and he never sought the spotlight.

In 1963, however, Chappell’s face flickered across TV screens and his name made the front page of the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. His paralegal, Marcos Hernandez, was acting as an interpreter for another lawyer’s client in a DWI trial. District Attorney George Gilkerson objected, claiming Hernandez had a conflict because he worked for a “bail bond lawyer.” Chappell, a spectator in the gallery, stood and objected to Gilkerson’s objection. An outraged Gilkerson charged Chappell, catching him with a left to the chin. Chappell hit the floor, and the incident soon resulted in Gilkerson leaving the DA’s office.

After the infamous punch, Lawyer Chappell’s advice to young attorneys was, “Carry a heavy clipboard to the courthouse for self-defense.”

In the mid-1970s, a Lubbock convenience store was robbed by a young African-American man. The police found a pair of gaudy yellow patent leather platform shoes the culprit had lost while running from the scene. The police detective got a tip that the shoes belonged to Byron “Lawyer” Chappell’s client, and the man was arrested.

At trial, the detective — known for his racially insensitive views — testified the shoes fit Chappell’s client. On cross-examination, the lawyer proposed the shoes might fit many people in the community, but the detective disagreed. Chappell —a former shoe salesman — reached into his pocket, produced a shoehorn, grabbed the shoes and asked the detective to try them on.

After vigorous objections from the prosecutor, the judge allowed the demonstration. The detective’s face turned red. He began to sweat and wiggle in the witness chair as Chappell approached with the offensive shoes and shoehorn, confident he had calculated the detective’s exact shoe size. Sure enough, the shoes fit the detective perfectly.

Unfortunately, other evidence convinced the jury to find the client guilty, but Chappell arranged a reasonable punishment. His shoe stunt — which publicly embarrassed the racist detective — became legendary in the minority community and beyond.

Chappell represented a young man named Milton Morales, who one day wandered into a convenience store shopping for sunglasses. The clerk called the cops and told them Milton had robbed her a couple of weeks earlier. He was arrested and went to trial.

Chappell cross-examined the clerk.

Q: You are positive Milton is the person who robbed you?

h: Yes.

Q: He robbed you and ran out of the store?

A: Yes.

Q: He ran out real fast, about as fast as you have seen anyone run?

h: Yes.

Q: You didn’t notice anything unusual about the way he ran out of the store?

A: No.

Chappell turned to his client. “Milton, run as fast as you can to the back wall of the courtroom.” Before the prosecutor could catch his breath, Milton began limpingasquickly as he could manage. It was painful to watch because Milton had been afflicted with polio as a child. One of his legs was about the size of a baseball bat.

The jury quickly acquitted Milton . The case didn’t make the papers, but Chappell’s people knew he had put another notch in his lawyer belt.

Chappell’s manner of speech was a curious blend of colorful colloquialisms, archaic adages and vulgarity.

The following is a sanitized glossary of “Chappellisms:”

- “This is where we’re sittin.”’ Chappell’s prelude to telling a client the unvarnished truth.

- “I need to feel the bumps on his head.” To convey a plea offer to a client.

- “I’ll be happy to sit next to you during your trial.” Discouraging words to a client slow to pay his trial fee.

- “Crazy as a peach orchard bore.” Description of any client who failed to follow Chappell’s advice.

- “He squealed like a pig under a gate.” Client’s reaction to an unreasonable plea offer.

- “Fifty years ain’t long if you say it real fast.” Sarcastic response to a prosecutor’s unreasonable plea offer.

- “Meaner than bar whiskey.” Description of a worthy opponent.

- “Two-bit politician.” Description of elected DAs or judges who failed to understand Chappell’s wisdom.

- “Thanks for the use of your courtroom.” Spoken with tongue in cheek to an unhelpful judge following a jury acquittal.

- “He doesn’t know s – – I from Shinola.” Description of an unhelpful judge.

- “But he’s got a good mama.” Used in plea negotiations with prosecutors. Some clients had few admirable attributes.

- “Pup.” Young associate lawyer.

- “I like her. She’s a spender.” Description of a pup’s wife. High-maintenance spouses were an incentive for pups to work harder.

- “Don’t tell me I can’t do that!” Chappell’s response to a pup’s adverse legal research.

- “You learn in’ anything?” Meant to encourage underpaid pups, in order to justify small salaries.

- “You hired out to work when you left the farm!” Advice to pups who complained of heavy workloads.

- “You better back up to that paycheck!” When pups failed to match expectations.

- “Don’t let them rot in jail.” It is impossible to render effective assistance to a jailed client.

- “All I got was his damn squawk box!” Chappell hated voice mail and answering machines, which would never be implemented in his office.

- “Make friends with your opponent. Then fight hard. The scars will be less likely to last.” Common Chappell advice.

- “Always satisfy your client.” Chappell’s most common advice.

- “It will all work out.” Chappell’s motto.